By Koaw - 2023

Mud pickerel is another common name for the grass pickerel.

BEST FEATURES FOR ID: (All of these features are discussed below in detail.)

Check the scalation on the cheek and operculum.

Check the snout length.

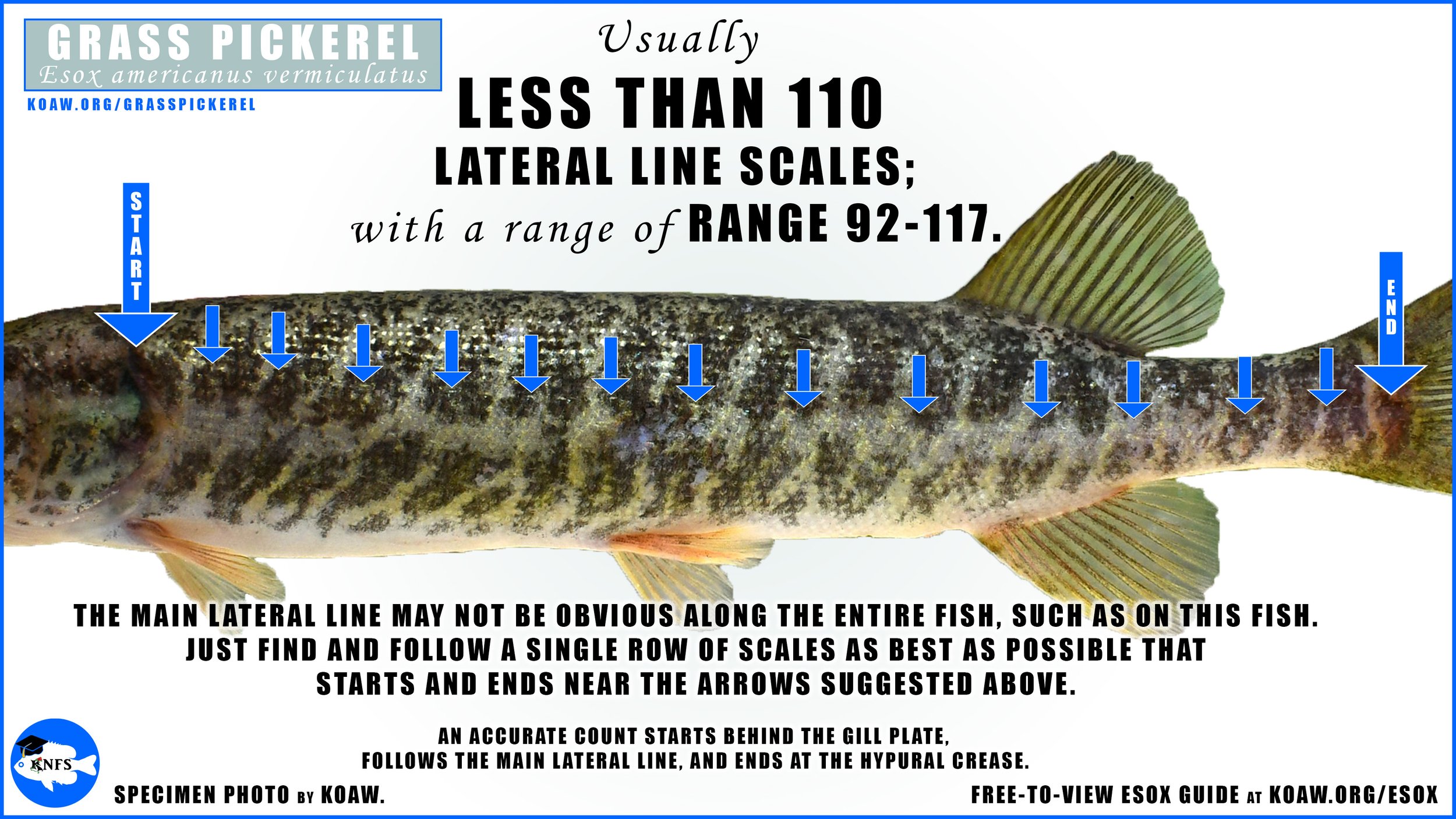

Get a count on the lateral line scales.

Get a count on the branchiostegal rays.

Compare the end of the maxilla vs. the position of the eye’s pupil.

Try the Quick Esox ID App that may offer a fast analysis, if needed.

Although color and patterning are very useful to assess when identifying the species within the genus Esox, there are countable (meristic) and measurable (morphometric) features that are more reliable, and as such, are the focus of this guide.

It’s important to examine more than one feature for confident IDs.

INTRO: The grass pickerel (Esox americanus vermiculatus) is one of two subspecies of the American pickerel (Esox americanus) [1] [2] [3]; the other being the redfin pickerel (Esox americanus americanus). Both subspecies are separated by range, though, a fairly broad intergrade zone exists in the Gulf Slope drainages between the Biloxi River of Mississippi and the St. Johns River in Florida; attempting to identify specimens to the subspecies level in this region is impractical and these specimens should, in most all cases, be regarded only as American pickerel (Esox americanus); [4] (see range maps in “LOCATION”.) Furthermore, intergrades possibly exist in the upper northeast most part of the range.

Although it remains okay to describe a grass pickerel as an American pickerel, it’s usually always best to be as precise as possible when describing species; if able to confidently designate a subspecies, then do so.

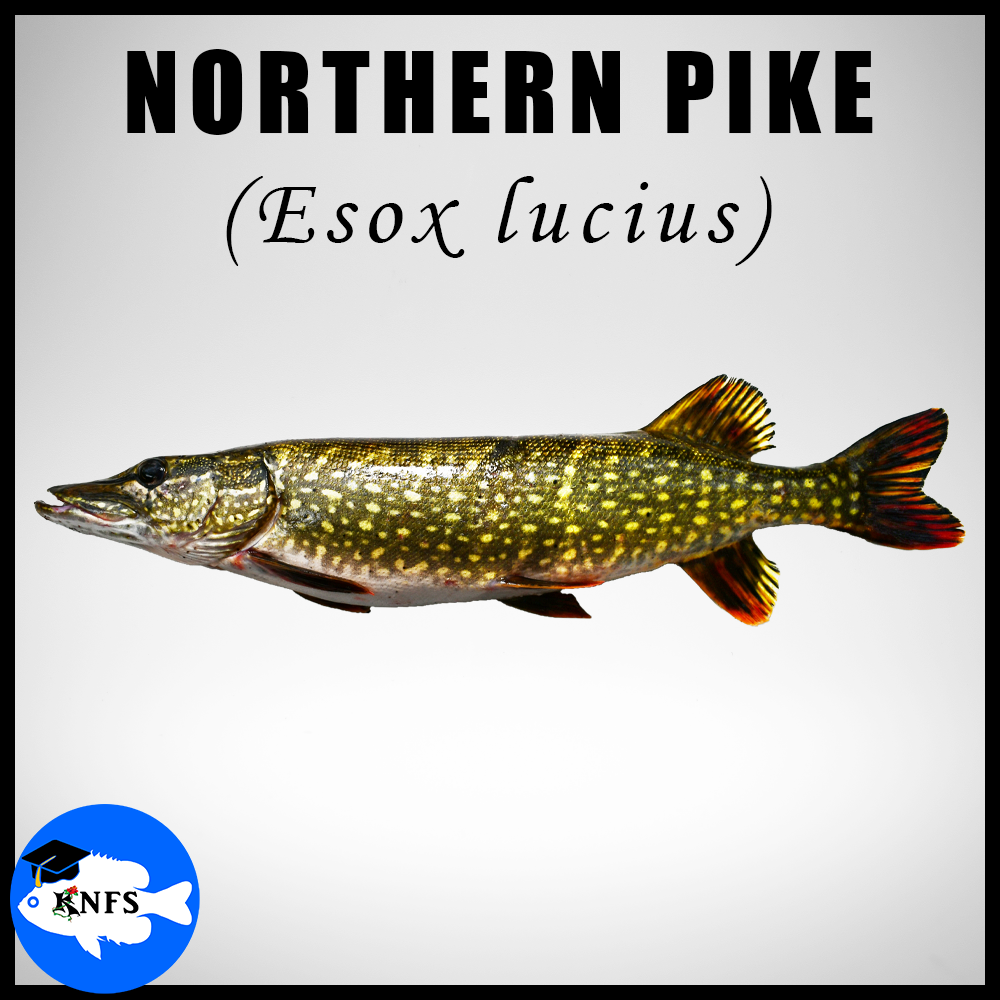

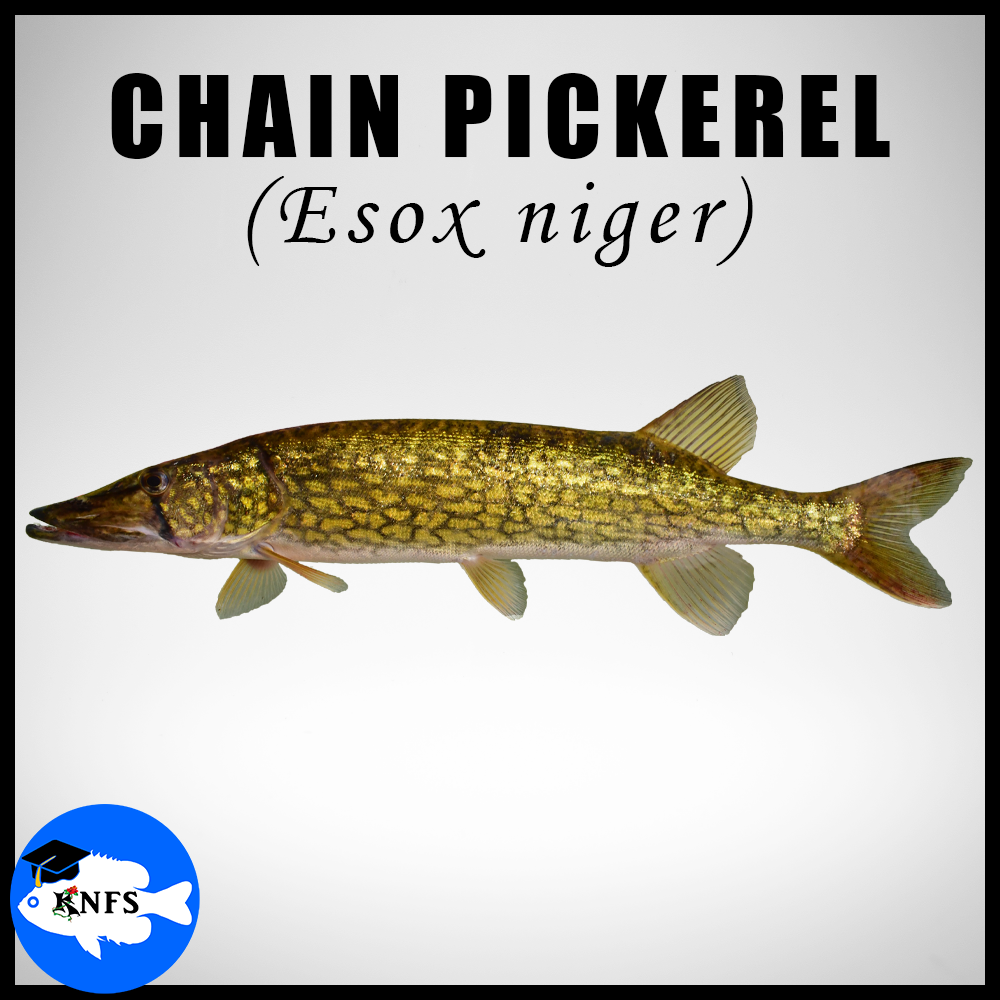

The grass pickerel is most often confused with the chain pickerel (Esox niger) and the northern pike (Esox lucius). Comparing the grass pickerel vs. chain pickerel will require evaluating the snout length as well as getting a count on the branchiostegal rays & lateral line scales. Grass pickerel vs. northern pike is generally resolved after examining the scales on the operculum and lateral line scale count.

KEY FEATURE #1 - SCALATION ON CHEEK & OPERCULUM: Of the North American esocids within the genus Esox, only the redfin pickerel (E. a. americanus), the grass pickerel (E. a. vermiculatus), and the chain pickerel (E. niger) will have a cheek & an operculum that are both usually nearly fully scaled, if not fully scaled.

These scales are best seen if the specimen’s head can be rotated underneath light, allowing for the shimmering scales to reveal themselves more easily. Aside from the youngest of juveniles, these scales should be readily visible.

If the cheek and operculum are mostly fully scaled, see Key Feature #2 to further help distinguish between the grass/redfin pickerels and the chain pickerel.

BODY: Like the other members of Esox, the grass pickerel has an elongated body with a single posterior dorsal fin above an anal fin of almost equal size. Also notice the deeply forked caudal fin, the low set pectoral fins, and pelvic fins set fairly far back, all traits of other esocids.

The redfin pickerel has a fairly long ‘duck-bill’-like snout with a mouth full of many sharp teeth. There are no spines within the fins and only soft rays.

Typically, there are between 17-21 dorsal rays, 15-19 anal rays, and 92-117 lateral line scales. [4] [5] (Lateral line scales discussed further below in comparison to other esocids within esox. All rudiments included in ray counts.)

KEY FEATURE #2 - SNOUT LENGTH vs. POSTORBITAL LENGTH OF HEAD: The grass pickerel has a slightly larger snout than its conspecific relative, the redfin pickerel. Yet, the snout length of the grass pickerel is still typically shorter than the congeneric relative, the chain pickerel.

For the grass pickerel, the snout length will usually not exceed the postorbital length of the head. The chain pickerel’s snout length will usually exceed or be very near the postorbital length of the head.

Of the data collected for this guide for grass pickerel, the snout length (SnL) fit into the postorbital length of the head (PtOL) for a mean of 1.17 times (PtOL/SnL) with a range of (0.95 – 1.33) including juvenile, subadult, and adult specimens. All specimens larger than 110 mm did not show a snout length greater than the postorbital length of the head, where a couple juvenile/subadult specimens showed only a slightly larger snout length than the postorbital length.

The snout length for chain pickerel fit into the postorbital length 0.94 times on average with a range of (0.78 – 1.13) including juvenile, subadult, adult specimens. A few specimens, both in the juvenile and adult categories had snout lengths that did not exceed the postorbital length of the head. [5] The trend seen from the data from this guide agrees with the trends illuminated in Casselman et al. (1986) and Crossman (1966). [6] [4]

PATTERN/COLORATION: Young and adults express very different colors and patterning. Even between mature specimens, coloration and patterning varies. Specimens may also flare-up or flare-down where colorations and patterns change rapidly along the body. Hence why a fish might be caught appearing fully barred along the body, and, after one minute, the bars may hardly be visible, or vice versa. That’s why meristics (countable features like lateral line scales) and morphometrics (measurable features like snout length) are such valuable features to use when identifying esocids.

Grass pickerel typically mature at around ~5-6 in (~13-15 cm) TL. Smaller females produce much fewer ripe eggs than larger females. [7] Adults are darker dorsally with an olive, brown, and/or tan color that becomes lighter to the cream or white belly. Mature specimens usually have many wavy irregular bars along the body, usually connected from the dorsum to the edge of the belly; inconsistent blotching may also be present on adults or even no real apparent wavy barring.

Young have a distinct, bright lateral stripe starting on the snout, extending through the cheek and operculum, and along the body to the caudal fin. This stripe fades as the specimen matures—on subadults it still exists but begins to become broken by the formation of barring on the body. Sometimes, especially when adult specimens flare down, a faded version of this lateral stripe reappears.

Unlike the very similar redfin pickerel, mature grass pickerel do not usually ever show red to orange in the fins but typically a yellow, amber, or dusky color. [4] This color is typically most present in the paired fins and anal fin. There is no spotting in the fins of the grass pickerel, as is seen in subadult/adult northern pike (E. lucius) and muskellunge (E. masquinongy), though very young grass pickerel will have a stacked pair of dark blotches at the base of the caudal fin as well as a bit of red or orange around these blotches.

The suborbital bar in mature grass pickerel is usually slanted towards the back of the fish, where the bottom of the bar is closer to the tail, though typically less slanted and with less curvature than the redfin pickerel. In juveniles, the bottom of suborbital bar is usually slanted towards the front of the fish, gradually changing the angle of slanting towards the back as the fish matures.

KEY FEATURE #3 – LATERAL LINE SCALES: When trying to identify young grass pickerel vs. young chain pickerel counting lateral line scales may be very beneficial, though tedious to count on very small specimens. This feature may also be beneficial if trying to further understand possible hybrids.

Grass pickerel do not show more than 120 lateral line scales, and usually less than 110. On grass pickerel specimens examined for this guide there was a range of 98-117 lateral line scales [5], which falls within the range of what Crossman (1966) found with a range of 92-117. [4]

Chain pickerel typically have 120 or more lateral line scales. Of the meristics gathered for this guide, chain pickerel lateral line scales range was 114-138 with only 7% of specimens having fewer than 120 lateral line scales. Casselman et al. (1986) report a chain pickerel lateral line scale range of 114-131 [6].

KEY FEATURE #4 – NUMBER OF BRANCHIOSTEGAL RAYS: A count on the branchiostegal rays is not definitive but often a fairly reliable feature to use to help distinguish the grass pickerel from other members of Esox (except vs. the redfin pickerel.) Typically, the grass pickerel will have 10-14 branchiostegal rays on a single side, where counts of 15 & 16 seldom appear.[4] Chain pickerel usually have 14-17 branchiostegal rays while sometimes showing 12-13, muskellunge usually have 16-20, and northern pike usually have 13-16. [6]

SUBMANDIBULAR PORES: A count on the submandibular pores is indeed a reliable feature to examine; (see adjacent photo.) Most all specimens of grass pickerel will show a count of 4/4, where there will be 4 pores on each side. However, this trait is not so handy to use for the grass pickerel because the pores are very, very difficult to see on the vast majority of specimens. Often there are flecks and spots on the undersides of the chin that are difficult to distinguish from pores to an untrained eye.

Furthermore, like most all the traits within this genus, this feature is not 100% reliable on its own. Small percentages of specimens from a population may show counts including 2,3,5, and, rarely, up to 6 pores on one side. [4]

Same as the grass pickerel, only the chain pickerel and the redfin pickerel will most often show 4/4 counts. The northern pike typically shows 5/5 counts with a common range of (4/5-5/6). Muskellunge typically show counts that almost always are equal to or greater than 6 pores on a single side.

SIZE: For most populations of grass pickerel, most adults will probably be between 5.0 – 10.0 inches (13 – 25 cm). Though, grass pickerel can become sexually mature in their first year of life, even as small as 4.0 in (10 cm). [8] [7] Max size is at least 15 inches (38 cm). [9] [10] The IGFA all-tackle world record is 1 lb 0 oz (0.45 kg). [11]

Click to enlarge.

HABITAT: The grass pickerel is almost always associated with dense vegetation. Preferred habitats are small streams, swamps, drainage ditches, and slow-moving water systems. This species can also be found in ponds and lakes, typically within weedy bays, and occasionally in rivers within slow waters. Though this subspecies is known to handle a wide variety of water pH, typically grass pickerel is found in more basic waters compared to the redfin pickerel that is usually found in more acidic waters.

LOCATION: The northernmost part of the grass pickerel’s range begins around Montreal at the confluence of the Ottawa and Saint Lawrence Rivers. The range extends through most of the southern half of the Great Lakes Basin including parts of northwestern New York, Pennsylvania, the southern half of Michigan, and the southeastern part of Wisconsin.

The range extends into the Greater Mississippi River Basin, including the remaining southern portion of Wisconsin, into parts of Iowa, most all of Ohio and Indiana, into Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. The westernmost part of Texas is range as well. West of the Pearl/Biloxi Rivers is considered grass pickerel range while the intergrade zone begins eastward. Most all of Alabama is considered an intergrade zone except the very northwestern portion.

Small populations exist along the Missouri River Basin along the northwester tip of Missouri and into a small portion of northern Nebraska, possibly extending almost to the western edge of the state. [4] [12]

There were reports of grass pickerel introduced into Washington State and Colorado (by unknown origins); this author cannot verify if any of these populations still exist. [13]

INTERGRADE ZONE:

Click to enlarge.

As mentioned in the intro, the grass pickerel (E. a. vermiculatus) is a subspecies of the American pickerel (E. americanus) while the redfin pickerel (E. a. americanus) is the other subspecies. A broad intergrade zone exists, or a zone where genes have been swapped between the subspecies. Specimens within this zone most often show intermediate features between the two subspecies.

This intergrade zone extends from the Gulf Slope drainages between the Pearl/Biloxi Rivers of Mississippi to the St. Johns River in Florida into peninsular Florida; attempting to identify specimens to the subspecies level in this region is impractical and these specimens should, in most all cases, be regarded only as American pickerel (Esox americanus).

There are isolated populations within this intergrade zone, specifically in certain areas of the Yellow and Blackwater Rivers, that show primarily redfin characteristics, [4] though I suspect genetic data would reveal intergrades.

It is suspected by Crossman that intergrades should exist, or at least soon will exist, in the northernmost part of the range. [4] I believe Crossman’s predication has some credibility after I analyzed a specimen observed in 2020 in the Richelieu River, just south of Montreal, that appeared to demonstrate intermediate features between both parent subspecies. [14]

KEY FEATURE #5 – MAXILLA VS. POSTION OF EYE: Though this comparison of the extension of the maxilla vs. the position of the eye/pupil is not as reliable when comparing grass pickerel vs. chain pickerel as it is for redfin pickerel vs. chain pickerel, there is still a slight trend worth noting despite the morphometric overlap.

The grass pickerel’s most posterior extension of the maxilla will usually pass or near the anterior edge of the eye, usually sitting between the anterior margin of the eye and the anterior margin of the pupil, while occasionally extending past the anterior margin of the pupil. Meanwhile, the chain pickerel’s most posterior extension of the maxilla more often does not pass the anterior margin of the eye and rarely exceeds the anterior margin of the pupil.

Conveniently, it’s typically adult chain pickerel that express maxilla not extending past the anterior margin of the eye. Adult chain pickerel express that distinct ‘chain-link’ pattern on the body and easily distinguishable from grass pickerel at any stage.

FISHING TIPS: The grass pickerel isn’t often targeted by anglers. However, nowadays, there’s a larger community of anglers that seek smaller species. This is a fun species to catch on light gear.

The preferred habitats of grass pickerel make this species a bit less desirable to most anglers. The prime spots are in areas where many anglers just don’t want to fish: swamps, rough creek edges, and very weedy backwaters and bays.

My preferred bait choices for pickerels are a weighted jig-head with a soft plastic (#10-#6), medium-to-large flies (#14-#8), and safety-pin spinnerbaits (#8-#4, #2-#1 for large specimens).

From my experience catching pickerels, one of the best strategies is to find an accessible spot of shoreline that has a weed edge against a pool or any open water. (Take care to sneak up on locations, as pickerels are often sitting shallow when water conditions are ideal and will spook easily.) Start with casting into the open lanes along the weed edges to work the open water. If there are emergent plants (like lily pads), selectively dipping and twitching a bait in the exposed holes will likely produce a fish, possibly a pickerel.

Considering the redfin pickerel is primarily a lie-and-wait predator, it means that these species won’t often be cruising around for meals (like largemouth bass do.) It’s important to work as much water as possible. Though, do have patience to work a single spot for five minutes or so before moving on. With some effort, often a pickerel will eventually shoot out of a hiding spot and snatch a bait.

REFERENCES:

[1] (Leseur C.A. in), Cuvier and Valenciennes, "Histoire naturelle des poissons. Tome dix-huitième. Suite du livre dix-huitième. Cyprinoïdes. Livre dix-neuvième. Des Ésoces ou Lucioïdes," vol. 18, pp. 520-553, 1846.

[2] J. F. Gmelin, "Systema naturae by C. Linnaeus pt.3," 13 ed., vol. 1, 1788.

[3] R. Fricke, W. N. Eschmeyer and R. van der Laan, "ESCHMEYER'S CATALOG OF FISHES: GENERA, SPECIES, REFERENCES".

[4] E. J. Crossman, "A Taxonomic Study of Esox americanus and Its Subspecies in Eastern North America," Copeia, vol. 1, pp. 1-20, 1966.

[5] Koaw, "Select Morphometrics and Meristics of Esocids," Koaw Nature - KNFS, 2023. http://www.koaw/org/esoxdatakoaw

[6] J. M. Casselman, E. J. Crossman, P. E. Ihssen, J. D. Reist and H. E. Booke, "Identification of Muskellunge, Northern Pike, and their Hybrids," Am. Fish. Soc. Spec. Publ., vol. 15, pp. 14-46, 1986.

[7] S. J. Kleinert and D. Mraz, "Life History of the Grass Pickerel (Esox americanus vermiculatus) in Southeastern Wisconsin," Wisconsin Conservation Dept., vol. Tech. Bull. No. 37, 1966.

[8] D. V. McCarraher, "Pike hybrids (Esox lucius x E. vermiculatus) in a Sandhill Lake, Nebraska," Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 1960.

[9] M. B. Trautman, "The Fishes of Ohio," Columbus, Ohio, 1957.

[10] L. M. Page and B. M. Burr, Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

[11] IGFA - The International Game Fish Association, "Pickerel, Grass - Esox americanus vermiculatus," IGFA, 2022.

[12] iNaturalist.org, "Esox americanus vermiculatus - Grass Pickerel," iNaturalist - Cal. Acad. of Sci. - Nat. Geo., 2022.

[13] iNaturalist Possible intergrade observation in northernmost part of range," iNaturalist.org / Cal. Acad. of Sci. / Nat Geo, 2020. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/53421292